Revolver Live! mit dem Kameramann Jürgen Jürges, im Rahmen der Diagonale Graz. Am 07.04.2024, 14 h. Mit Christoph Hochhäusler und Nicolas Wackerbarth.

Hannes Brühwiler: When I first met you, you mentioned that you would have loved to be a poet in the 19th century. Do you see yourself more as a writer?

Nathan Silver: No. When I was 12 I started reading Rimbaud’s poetry and I fell in love with it. And so I learned French around that time and I wrote hundreds of poems in French. So I went to live in France when I was around 16 for high school and when I got there I thought everyone would be obsessed with Baudelaire and Rimbaud and all these guys, but the people there were like, oh yeah, Baudelaire and Rimbaud. And I got really disillusioned. So while I was there I went to the theatre, I started reading Artaud and all these people. And then when I was in college I did an internship for Richard Foreman. You know Richard Foreman? In high school I’d seen one of his plays when I was visiting my brother in New York and I thought he’s obsessed with the same kind of poets as me. So I thought, oh I got to work for this guy. So while I was in school I did an internship for him and he told me theatre’s dead, nobody comes to see my plays anymore and I’ve been doing this for 30 years. And so I got very disillusioned and he kept telling me to watch movies by Fassbinder and Pasolini…

Zsuzsanna Kiràly: Had you heard of them before?

NS: I’d heard their names but I never actually sat down to watch their movies. I think I watched part of “The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant”, but I didn’t get through the whole thing. So then his theatre was really close to Kim’s video store. After my internship I’d go around the corner to Kim’s and I would rent these movies and after a while I said, this is much more interesting than theatre. This was around ten years ago… so people were still going to small movies in the city. Now it’s much more of a struggle to get people out to the movie theatres.

HB: Were you aware of the 90s independent filmmakers? Soderbergh, Tarantino, Haynes?

NS: I never considered the American movies to be art. I had this ideal of art, like Rimbaud. I thought you had to be this struggling artist, like Jean Genet. So I was more interested in films by Cocteau. When I got into school, people convinced me to watch “Boogie Nights”. I came to appreciate it. But it’s not like I was trying to emulate Tarantino or any of those people. I never thought of them as artists, I thought of them as people who were able to make money.

ZK: You remember what you liked in the poems? Do you see a relation to what you are writing about now and shooting?

NS: Yes, they are all about anxiety. With Baudelaire it’s often the same theme or similar theme – that is, having anxiety or panic. That’s what I’ve always loved in art, from Edvard Munch to Strindberg to Baudelaire. And then with Rimbaud I love his idea of confession. I don’t know if I’ve really brought that into my movies yet, but I do take a lot from my life. When he wrote “A Season in Hell” there is this wonderful confession. And that’s maybe why I like to make these movies that draw so heavily on my life. I always loved the paintings of Brueghel, I loved his idea of the carnival of life. I love Michel de Ghelderode, he is a Belgian playwright who has the most grotesque plays imaginable. I guess it’s kind of similar to what I said about wanting to be a 19th century poet, he kind of has this old school artist ideal of himself.

HB: For Baudelaire the city was very important and the character of the flaneur. I wouldn’t say that your films are populated by flaneurs but I can see similarities. We may not see the city in every shot in your film, but we feel it in every image.

ZK: In “Soft in the head” you see the city very briefly. When she is walking…

NS: That’s the one scene.

HB: That scene is almost liberating. We are outside and we follow her and we’re not in tiny rooms any more.

NS: This is one of the longest shots of the movie. She is just walking and walking. The first time she is walking at the beginning, we hold on it for a very long time. And then there is a long shot towards the end where she’s dragging Maury down the hall and then you have her holding him. So I like these two bookends, you have her walking down the street and then have her going down this hallway, and it’s a very claustrophobic hallway to boot.

ZK: It ends ambiguously. It feels like you want to play with us – is he dead or do you want to raise concern? And I personally really like the gentle gesture at the very end, I really really like that. How did it come about?

NS: I never intended him to be dead. I always have reference movies I take endings from and one of them is “Modern Times”. The ending of “Exit Elena” where she’s walking away is straight out of “Modern Times”, you know what I mean? She is basically walking into the future. And then the other movie ending I love is “Belle de jour”. The man has been shot outside and he’s paralyzed, she is taking care of him and then you hear the sleigh bells and he gets up from the chair and everything is fine. The idea of Maury moving his hand I always wanted… it’s this artificial ending, it’s almost a holy thing that he’s fine, that everything is okay. But it’s more subtle than in Buñuel’s ending.

HB: This reminded me also of Roberto Rossellini’s films. Like the miracle ending in “Journey to Italy”.

NS: It’s the exact same thing. I love endings like in “Pickpocket”, where he comes around and he says: “Oh Jeanne, how long did it take me to find you.” You don’t expect that. It’s almost like it has a certain holy quality to it. At the ending of “Fear Eats the Soul” you start to expect that too. But Ali passes out at the bar and he gets to the hospital and then you realize the vicious cycle is just going to continue. Fassbinder teases you with a potential miracle that they get back together and that everything will be okay, but then it’s not. That’s something I’m thinking about for future films, like taking that miracle ending and twisting it again.

ZK: In this context your films have a very hopeful ending… Even though they seem very very desperate and confused at first.

NS: I’m very happy to hear that.

ZK: Thinking e.g. of the cat who is maybe better off with Elena .

NS: And also the cat is in the same situation as Elena. That is established at the beginning when my mother compares them. So it’s this funny thing: now Elena and the cat are free but their future is uncertain. And that’s what I love about the ending of “Modern Times”, it’s bleak and at the same time it’s something of a happy ending. I know that Fassbinder was obsessed with the ending of “Suspicion”, which is another miracle ending. Because she thinks that he’s going to kill her but then he explains everything and they are absolutely happy, but you know their relationship has been destroyed more or less.

ZK: You always have female characters as your leads. What you can express better with female characters than with male characters?

NS: It wasn’t a conscious choice. With “Exit Elena” I knew I wanted to work with my mother and my girlfriend at the time and I knew I wanted to put them up against each other. Also whenever I watch movies I always find myself drawn, not like sexually drawn, but I find female characters much more interesting. With “Soft in the Head” it was Maury who was supposed to be the main character. But then after all the rehearsals and when we started shooting, it somehow became clear that Natalia was the way to connect the two worlds, the world of the homeless men and the world of the Orthodox Jews. She would be crazy to some degree but people still stick with her. I feel like when you have a male character who is in pain, it’s very hard to stick with him. There’s something interesting in the fact that people are a little more forgiving about madness with women than they are with men…it’s actually disturbing, come to think of it.

HB: Do you think this is something romantic?

NS: It might be. I don’t know. That’s maybe the way we are wired. We might think that women are more hysterical. This is not the truth. With Fassbinder for example women are technically allowed to express their emotions, whereas the male characters keep things bottled up. You think about the character of Hans in “Merchant of the four seasons”, he’s all tension. Then you have female characters, like Petra von Kant who is also all tension but she expresses her emotional tension throughout in all sorts of ways.

HB: A lot of his films are about female characters who suffer.

NS: He is able to express something else and I think there is this vulnerability that is wonderful with all his female characters, and I admire and am drawn to that.

And maybe there is a connection to my mother, who is so much more vocal than my father on a lot of levels. I realize the way that she tells stories is the way I want to tell stories. She can’t keep on track, she makes things a little absurd, it’s not quite clear what she’s after but she continues to tell the story. And I think that I took something away from that and I always apply that to my characters. And I also don’t like manly men, I don’t like the group in Cassavetes’s “Husbands”, I could never hang around those guys.

HB: Speaking of female characters, Lars von Trier said that he writes his characters first as male characters and then switches them to female. How do you create female characters?

NS: A lot of the time, I base the characters on the actors portraying the characters. I start talking to them about what I know about their life and then we create a character out of certain details and they make up some things in order to create a distance from who they actually are.

HB: Do you enjoy acting in your films? Or is it out of a necessity?

NS: It started with “Exit Elena”. I wanted to keep the cast and crew as small as possible and I also wanted someone who was like me. But I didn’t want to have to deal with another actor, so I knew I was the only person who could play that character. And now in every movie I make, I either appear in it or there’s a character with my name.

HB: How did you work on set for “Exit Elena”? Especially with the cameraman?

NS: We spent the first week and a half shooting all the scenes before my character entered. So my cameraman and I knew how things were going. After each take we would re-watch the footage, a lot of the times without sound because I could remember what people said more or less. I wanted to see where the camera was at different moments. And then I would basically go in for inserts. We’d shoot long, long takes, like for an hour.

ZK: You just kept going?

NS: Yes. Kept going. In “Uncertain Terms”, I was supposed to have a larger part but I found it really hard to direct myself in this movie. And I don’t know why, I just couldn’t do it this time. And so I cut my character more and more. It was interesting because in “Exit Elena” I felt completely at ease. I knew the character well and what I wanted to do. I could direct a scene from within, I could push people’s buttons. I could just push it in any direction I wanted to.

HB: For example in the card game scene in “Soft in the Head”, the actors didn’t know who was filmed and who wasn’t?

NS: It’s a great way of doing it. I think a lot of directors do it that way, because it makes it feel like a situation instead of a set and you can then steal all these little moments. You can build something that actually feels like a documentary of a fictional situation. That’s how I think about these movies, documentaries of fictional situations. I can craft all these elements and then just document them, instead of thinking about just setting all these things up and then setting up a camera and then capturing what I planned to capture. No! I will set a situation up and then figure out a way to float the camera through a situation and find little details that hopefully add up to something in the end.

ZK: You rely on the fact that the actors won’t forget about these partially half-constructed situations from rehearsals, and at that point in the process you can let the moment happen or make it happen. Do you think this approach works with non-actors and actors alike? Or is it distinctively the mix of non-actors and actors that makes that possible?

NS: After a while everyone gets on the same level. At first everyone is all over the place, but after a few days on set people start to understand what it’s all about. I can’t impose that. It’s just about people actually living through these situations and that is the thing about tight shooting schedules. It’s harder to have that come together because you need at least three days for people to warm up to the movie. And that’s usually why I don’t use any footage from the first day of the shoot.

HB: How many days do you usually shoot?

NS: They’re all around like 15 days. And then two or three days of pick-ups. That’s not that much time, but there is always that first day, which I never use the footage from. So ideally in the future I’d like to set up a week where we would just shoot scenes, I don’t know if they’re going to end up in the movie or not, and we might have to reshoot them but everyone is getting on the same page. They would be the scenes which have the most characters together in the same place. So everyone starts to get an idea of how it’s going to be. But rehearsals… people don’t put as much into rehearsals as they do into the actual shoot. So I’d like to have a week where I shoot simply to get the movie on the right footing. That’s how I would schedule it. And that’s what money would give me…

ZK: Yeah, money always gives you time.

NS: I don’t care about equipment, I just want more time so that people would be able to get acclimated.

HB: Would you like to shoot in chronological order?

NS: That would be great. But it’s not possible with the budget and schedules I have currently. It would also mean that the movies would start off terribly because of those first awful days.

HB: And what about sets and locations?

NS: “Soft in the Head” was shot in my apartment and “Exit Elena” was shot mostly in my parents’ house. “Uncertain Terms” was shot in my parents’ new house. So it’s always about availability, availability to go back to do reshoots. If you have to pay money in order to get a location in the States, you need to have insurance and have to be in and out at a certain time, so it just makes everything a pain in the ass. Filmmaking is emotional, the story is the emotion. It doesn’t really matter where it takes place as long as the characters’ insanity is coming through. Good sets might add something to it, but right now, without the budget to do that, I would rather shoot in my apartment instead of shooting those scenes in potentially more fitting spaces but with more restrictions.

HB: In “Soft in the Head” most of the shots are focussed very tight. Did you plan that before?

NS: Oh no, not at all. The first day of shooting there were wide shots on tripods. But then at one point, the DP and I acknowledged the tripod wasn’t working, so we went handheld. When we started shooting scenes in the apartment there were 3 cameras going and whenever we went wide a camera guy would be in the shot. We had to just have it very tight. And it worked for this claustrophobia. That sort of dictated every decision because we realized that that was the atmosphere of the movie.

HB: When did you decide to use CinemaScope? Your first film was 4:3.

NS: I think 16:9 is just mediocre. Either it has to be square or CinemaScope. I don’t know what it is. I want to like 16:9 but it just doesn’t feel like anything to me. But I’ve had a lot of arguments with people about it, that CinemaScope is for shooting landscapes etc, but I just have no feeling for 16:9. I think it’s a useless shape, I don’t like it. I love 4:3. My most recent feature “Stinking Heaven” was shot in 4:3 and we used an old analogue video camera.

HB: I’m surprised how few people use this format nowadays.

NS: Bujalski in “Computer Chess” used it. And Gus van Sant in “Paranoid Park”. I don’t watch movies when I’m done with them. But there are certain screenings of “Exit Elena” where I pop my head in just to see it on the screen, because it’s so off-putting to see 4:3 on a big screen, like it should not be projected. That movie was shot on standard DV. It has the feeling of a home movie, it’s funny to see it projected in theatres. I almost feel like I should destroy all the links online and just have it shown in theatres, because it’s almost anti-cinema.

ZK: Could you ever shoot something where there are no people in the frame?

NS: No! I don’t think so. I hate going to cutaways. I hate coverage. If you shoot without coverage then you’re shooting what you think is necessary, not what people think is safe.

HB: And it’s also a different way of editing.

NS: Yeah. You’re forced to make decisions you wouldn’t have made. You’re forced into these corners. I think you should shoot without coverage. (laughs)

HB: You said you cut out a lot of material of „Uncertain Terms“. When I watched the film again I was struck by how fast the film is. Some scenes are barely two seconds long.

NS: I worked with Cody again who edited „Exit Elena“ and „Soft in the Head”. It’s always about what works and you get rid of the rest. I always think of that quote from Pialat’s editor, about how if he didn’t like a scene he just cut it out. Even if this made a hole in the story, he didn’t care. The pace is also dictated by the fact my movies aren’t scripted, so they might meander a bit at times, and you have to keep up pace. You don’t want to lose the audience so you keep the movie moving.

ZK: How do you prepare the shots with the cameraman?

NS: „Uncertain Terms“ was shot with two cameras and because Cody is both the cinematographer and editor, he knew what we needed for the edit in order to make it work. So we would grab shots for each character. Usually we would start by focusing on the most important characters for the scene and then go in and grab reaction shots of the others.

ZK: How do you position the two cameras in the space, from wide to close-up shots?

NS: It depends how big the space is. In „Soft in the Head“ we would usually have one camera doing wider shots and one doing close-ups.

ZK: „Uncertain Terms“ opens up to the world around. There are many more exteriors, there’s more air coming in. It seems the characters can breathe more, even if sadness resonates around them. The whole setting, with the forest surrounding the house feels isolated in a very quiet way. The film feels in general a bit more toned down…

HB: The camera also feels much calmer.

NS: To be honest we shot some scenes with the girls that were more hectic and that hectic quality just didn’t work in the edit. So all the scenes that have that hectic pace and tension didn’t fit eventually. We tried to force it and tried to get some more force in the house, but in the end it didn’t work.

ZK: Are the chapters a kind of signature style of yours in editing?

NS: I like chapters a lot. Yes.

HB: Which brings us back to literature.

NS: Yes, that’s true. In my short film “Anecdote” I would fade to white and a narrator would talk about the characters. I think I stole that from “Querelle”. I remember Fassbinder saying that in order to keep the audience awake he would go to white with black font instead of black with white font. As if to shock the audience awake. And of course “Querelle” is an adaptation of a book and it’s very literary. That’s the movie which most influenced “Anecdote” and led me to use chapters. Whenever I start a new project, I usually search through novels to get ideas.

ZK: Literature is a huge influence, but you once said, that you don’t like to write a script. Do you write for yourself but then don’t use it for your films?

NS: Mhmm… I write outlines. And they’re a pain in the ass, I hate writing at this point. I used to love writing but now it all goes into filmmaking. It’s not like I’m not obsessed with images, though. I’m not trying to be Tarkovsky. When you are writing holed up in your apartment, it’s like a prison. I’d rather be out with people talking to them and seeing crazy things going on. I like the fact that Pialat started off as a painter but his movies are not very painterly and his images are often quite plain. I like that. He has moments which are just beautiful but not in classic way. Watching his films, it’s not like you’d immediately know that he had studied fine arts.

ZK: What attracts you to people and makes you wish to have them in your film?

NS: I guess the people I cast remind me of someone I’ve known or someone who could be part of my life. Sometimes I don’t know what that is or why that is, but I just find myself attracted to these people.

ZK: Speaking about language. In your films it is a lot about what people say more than about how and with which specific words. Nevertheless I have been wondering if you ever tell the actors exactly what to say, or if they always improvise?

NS: When I cast people I don’t want to have to hold their hand through the movie. I just want them to be able to speak freely. In the beginning I found directing very frustrating. I thought everything had to be done in a sure-handed, meticulous way. Now that does not interest me at all. I find it completely boring. I don’t want to shoot things the way they are in my head. My movies are about capturing the insanity of life.

ZS: The title „Uncertain Terms“ describes the state of all your films very well.

NS: Absolutely.

HB: We talked about the endings, but what about the beginnings? In the first sequence in „Uncertain Terms“ we follow a young woman through the woods. The moment when she turns to the camera and we see that she is pregnant is quite striking. Can you talk about this opening shot?

NS: Basically what happened is that we shot for 14 or 15 days during the summer and then we edited it and we realized that we had to cut out a whole chunk of the movie, of the story. So we rewrote certain scenes and went back for pickups. We knew we wanted to start with her walking in the woods. It was Chloe Domont’s idea, she thought this was the sharpest way to get into the movie. All my films open in the middle of things and we have to figure out where we are and what’s happening. I think this new film has a more classical structure than „Exit Elena“ or „Soft in the Head“, but we still have to look for clues as to what this is, where we are, who to follow.

HB: And the films end also in the middle of something.

NS: Yeah. I like this idea. Someone said to me that there are no beginnings or endings in my movies. So you can watch them all, one after the other, and it’s like a collection of slices of life and in the end there will be potentially a pie.

ZK: There are always two people in the last image, they’re never alone.

NS: Yes, that’s true. Although in my newest film, „Stinking Heaven“, that’s not true.

HB: „Uncertain Terms“ is based in part on your mother’s life and also on the interest of your co-writer.

NS: My mother, when she was 15, got pregnant and was sent off to a home like we see in the film. In reality, it was much more like a prison. In „Uncertain Terms“ we wanted my mother to run a home that is more like a make-shift facility for these girls to give them what she didn’t have in her real life. The fact that Chloe always wanted to make a film about pregnant teenagers worked very well with the story of my mother. Initially it was only about one pregnant teenager with whom my character comes home and my mother taking care of the baby. That’s the origin of the movie that I almost completely forgot until the lead actor, David, reminded me at a festival recently. The funny thing about the movie is that it is constructed like a melodrama – the construction is artificial. You have this character who should not be there entering the situation and really causing disorder in the house.

ZK: I like your mother in the film. She develops along with your films, we get to see a calmer facet of her.

NS: In „Exit Elena“ we were reenacting something that had happened to a certain degree in our life. With „Uncertain Terms“ she acted a part she hadn’t lived – she never ran a halfway house. And here she is much more tender, because she is looking after all these wounded teenagers. Also, there is no husband figure to argue with. In fact the only person she has to argue with is my character. She is not a trained actor but she reacts to whatever is put in front of her. She is a natural actress.

ZK: You said that you are constantly improving and rethinking your working process. About „Stinking Heaven“ you were saying on another occasion, that you were shooting and editing at the same time. Could you talk a little more about that?

NS: With my new film „Stinking Heaven“ we decided to shoot four days a week, edit for three, shoot for four, edit for three. I didn’t have a day off which was great but at the same time I thought I was going to lose my mind. We rewrote the outline according to how the edit was going. I’d say, as I go on making movies, I would like to have three days of shooting, and four days editing.

Now I’m working on a project that I’m scripting, there will be improvisations but basically we’re going to work off a script. I always react against the last project. With „Uncertain Terms“ I was reacting against „Soft in the Head“ which was a lot of improvisation. „Uncertain Terms“ was much more scripted. I then made „Stinking Heaven“ which was a lot more improv, a lot more chaos, a lot more insanity. And now I’m reacting to that with a script. It’s about constantly reacting to yourself, fighting against yourself… like a healthy relationship. I guess I feel right now that movies are my wife.

ZK: It’s a way of shooting that’s not very common and it’s certainly not for everyone.

NS: It’s giving yourself over completely to the movie rather than dictating what to do. Because I feel sometimes that people are too adamant about making something that is their so-called vision. I mean your vision comes to you naturally. People talk about control, about storyboarding. And that’s fine, if that’s how you see the world and if that’s how you have to deal with the world. I don’t understand the world, I don’t understand how people are going to react in a certain situation. I want to show the hectic qualities of being a human rather than a constructed quality that I see in movies and that’s what I’m after in the end.

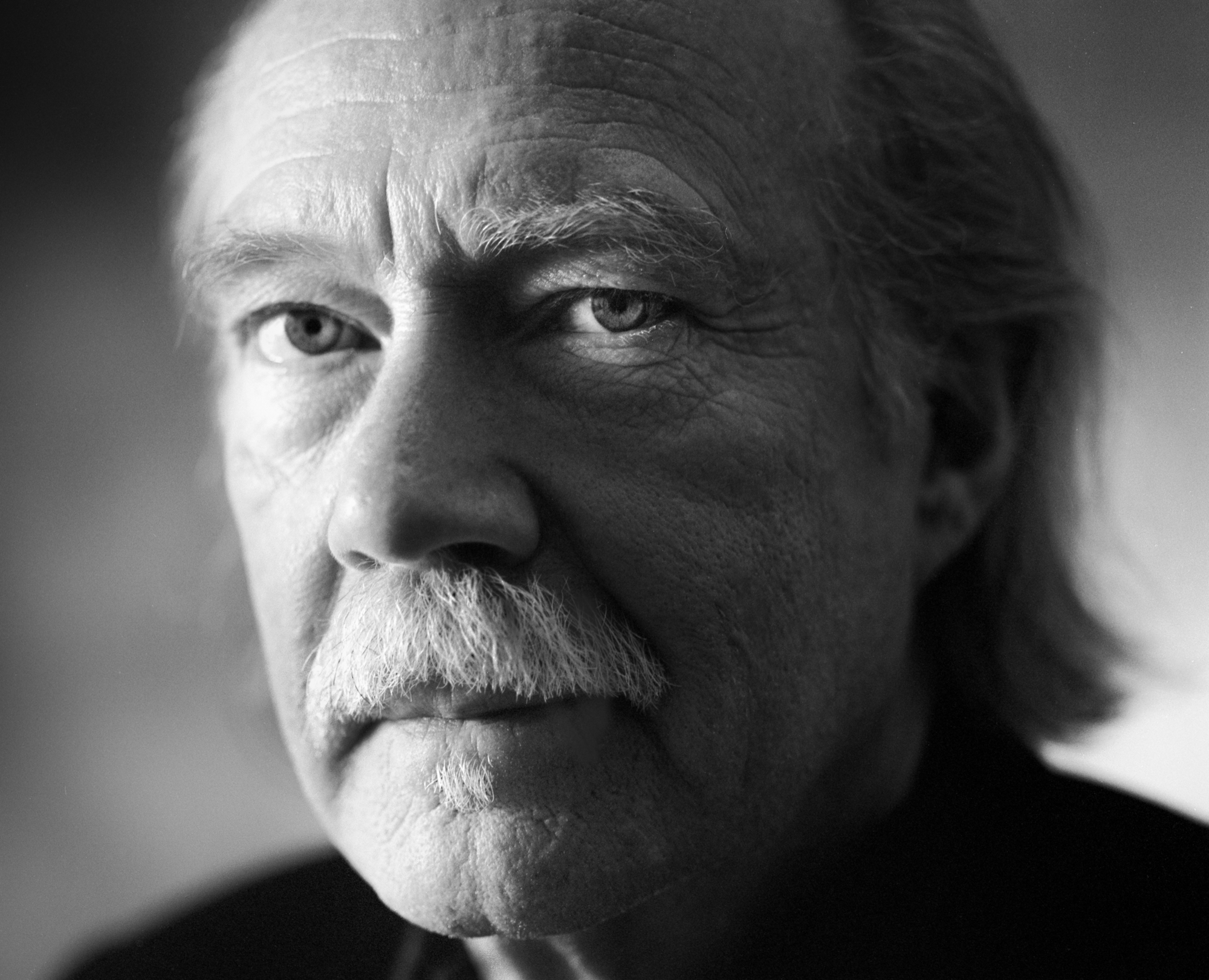

Nathan Silver (filmmaker, USA)

in conversation with Hannes Brühwiler and Zsuzsanna Kiràly

(first published in Revolver, Zeitschrift für Film #32, May 2015)