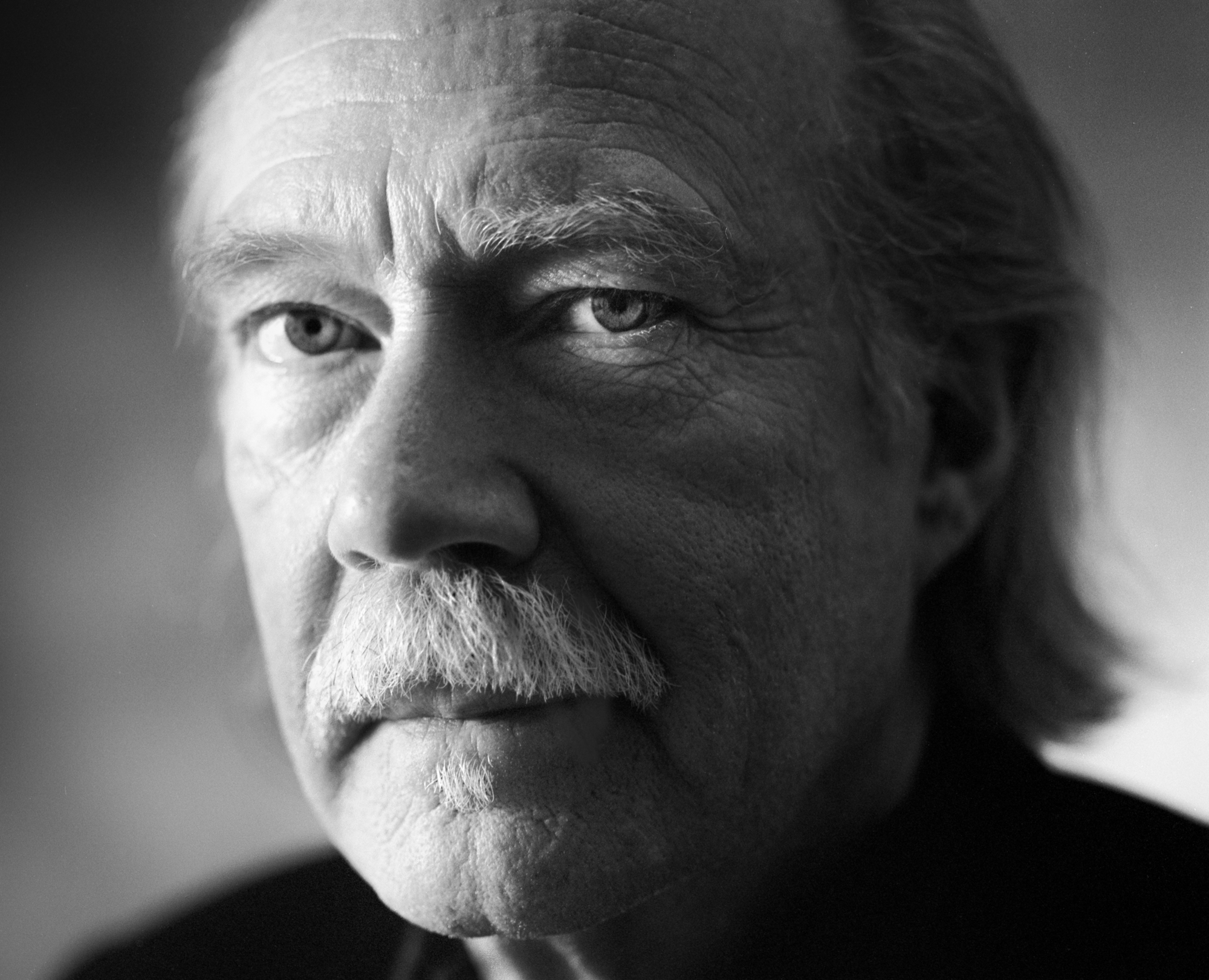

Revolver Live! mit dem Kameramann Jürgen Jürges, im Rahmen der Diagonale Graz. Am 07.04.2024, 14 h. Mit Christoph Hochhäusler und Nicolas Wackerbarth.

Zsuzsanna Kiràly, Revolver: When you walk and see things, what gives you usually the impetus to film something? Is there a divide between “I see as a person”, “I see as a director”, “I see as the cameraman”, or is there no more distinction of what and why, after many years of filming?

Jem Cohen: It’s very instinctive and I think there’s very little separation between my eyes as my eyes and my eyes when I’m directing. My sense of directing is, I hope, connected to what Dziga Vertov said, which is: “There’s no need to say action. It’s always action.” And that’s a very different kind of approach to filmmaking than is taken by many directors who work in more traditional “film industry mode.” So, I don’t always even think of myself as a director because when I’m working on a project like Counting at least, I’m not really controlling things. I’m not necessarily directing things. I’m accepting them and sometimes chasing them, and then molding them in the edit. That is not the only kind of film that I make. But it is a tradition that I’ve celebrated over 30 years now. The tradition is perhaps more familiar to people in terms of street photography, still photography. But it’s also a cinema tradition, even though that’s often forgotten.

R: Do you map out what you want to do next, or does an idea come up which you then go shooting, gathering images for a new project?

JC: It’s a mix of the two. Museum Hours was in some ways very different, because there are scenes with actors, scripted scenes. There’s dialogue that has to be conceived and activated. And I needed a crew. But I love to shoot and I love to wander and it’s a very important part of my life and I don’t really separate the filmmaking from the rest of life – nor do I separate one kind of film from another. So, I may shoot for years gathering material and not have a particular project in mind or I may embark on a project and look back into the archive for material that already exists. Or, at a certain point I may go looking for some very specific things and know that they are intended for a particular project. But, all of those distinctions are somewhat blurred and it’s important to me to blur them because the filmmaking is part of how I navigate in the world. I’m giving you vague answers, because the truth is that I don’t approach things from a very theoretical standpoint. Filmmaking is very natural to me at this point. And I need to be able to make things on a pretty constant basis and much of traditional filmmaking is based around a process in which you have to have extensive meetings and you can sometimes be forced to halt or never even get to begin, if the money isn’t there. And that’s just not possible for me, to depend on that kind of structure. But, on the other hand, you know, I would also love to be able to make more films with crews and a somewhat larger apparatus and permitted locations and all of that. It’s very, very difficult to raise the money for it. There’s virtually no support in the United States for uncommercial work, for work without celebrities. And, so I had to develop other strategies. That’s the reality that I’m faced with.

R: US or Europe, both systems bear a fair amount of regulations, obstacles, challenges and freedoms of sorts…

JC: It’s hard for me to distinguish at this point what is a matter of choice and what is a matter of necessity, but once I got used to being able to make films all the time, on my own if necessary, then it becomes difficult to shift gears and find myself possibly waiting for months or years to get that proverbial green light from others. It’s unfortunate that it’s a lot easier to fund a predictable and stupid film with name actors than it is to fund a mysterious and unpredictable and surprisingly different film that happens not to have any of them. And there’s something very perverse going on in the increasing dominance of commercial values. When I started out 30 years ago, people would say, “well, you know, you’re gonna have a hard time with this in America but you can go to Channel 4 in the UK to show it you can go to different European avenues where they understand this kind of thing”. And now, increasingly, I’m told that these avenues are likely to be closed as well. So, it’s not a choice that I’m happily making, working largely outside of the system. It’s a choice that I’m making because I need to make films. And, you know, it’s a battle.

R: Speaking of European funding, Chain was made with ZDF/Arte in Germany and I wondered if I missed something, or didn’t you work with them anymore after that?

JC: Well, I had a wonderful champion at the time, Doris Hepp at ZDF/Arte. And she was willing to take a risk. I mean, she purchased Chain essentially for a documentary slot and she believed in the film, but she was also, I think, quite interested in the aspect of it being a hybrid film. It is both documentary and narrative. She had the guts to show it, but it wasn’t something that necessarily translated into a broader relationship. I’ll always be thankful to her for allowing Chain to come into the world, because that was the film’s primary support.

Of course I would love for Museum Hours to be broadcast in Europe. It’s a largely German language film, and it represents a lifetime’s worth of thinking about why art is important, about the lineage between cinema and other arts; about why art matters in daily life, and it has proved to be a very accessible film for different kinds of viewers. So of course, I want it to be broadcast. But as I said, the business side is very mysterious to me and I’m not so good with the kind of hustling it takes. I put my energy into making films and I’ve made somewhere between sixty and seventy of them. And maybe that’s the best I can do. I wasn’t born to be an entrepreneur or a salesman and I also don’t consider everything I do to be a masterpiece. I don’t expect to get into every film festival. I know that every programmer is inundated with many, many, many more films than they can take on. I don’t come to this with some sense of privilege or expectation, but I can’t say that I’m not disappointed sometimes. Many of the films I’ve made are short films. Some just a few minutes long. Many of them are done in a relatively primitive way. I would be ecstatic to be able to do one feature every three or every four years; while others are able to make a feature film every year or two.

R: That means that you usually work on multiple projects at the same time?

JC: I almost always work on multiple projects. Some of them are more extensive. For example, I’ve been working on one for over twenty-five years, a project about 42nd Street, Times Square, in New York that I mostly shot in the late 1980s and early 90s. I think that material gets more interesting as time goes by. I’ve tried, every once in a while, to fund it and I’ve been to these obscene pitching market events and people were apparently not interested. So, you know, some things like that are just going to have to wait until there is some money, because I can’t do them entirely out of pocket.

R: To come back to Counting, could you walk me through the process, how you assembled those exact images. I know that you were traveling and you took the images between the years of 2012 and 2014.

JC: Stepping back into the depressing part a little bit: I didn’t pick any of the locations as there was no budget, and no support in terms of production. I went to places where I had jobs or I had a festival screening or something and I was limited by that. But, I was also lucky that I was able to get to Russia and Turkey at all, which I’d wanted to do for many years. You take these kinds of limitations and you try to make something interesting out of them. I became fascinated by the question: if I were to be randomly dropped into any number of particular places around the globe, would I find certain commonalities? Would I find interesting contrasts? It became an experiment, taking the temperature in a prescribed time period in a number of radically different locations, and then finding ways to tie them together and study the reverberations.

The very last chapter called “Skywriting”, number 15, was actually the first one I made. I made it as a kind of private project, because I was very sad over the death of Chris Marker. And, in a way, it was a tribute. More accurately, it was a kind of letter to him. I had been in occasional correspondence with him over at least ten years and met him a few times and his work was tremendously important to me. And he had been kind about my films. So, I was very saddened by his passing, but I was also reminded of how inspiring he was. Not only as an individual, but as part of a tradition, which I think encompasses people as far back as Dziga Vertov, Joris Ivens, or Humphrey Jennings, and on to people like Agnès Varda, James Benning, Peter Hutton, or Chantal Akerman. And, so I wanted to make a project that was in a way a specific recognition of a tradition. You could include many others in it as well. Deeply independent filmmakers who integrate politics in their work because it’s inherent – to the landscapes they film, to the very mode of production, to life itself. So I was not in any way trying to make a Chris Marker film or to link myself to his work. But I was hoping to kind of continue a dialogue that was no longer possible with him, a dialogue with a tradition. So I made that first piece, I made another, I made another.

I wasn’t sure that they would be part of a feature, but I began to be interested in the links and echoes between the separate units, and I was also interested in addressing certain themes. Some of them were personal, in a way that I hadn’t done before in my films. Some of them are political, in a way that I often do in my films. And some of them are purely visual. And I’ve often said in discussing the film that it’s a kind of marriage of city film and essay and diary…

And it also has a certain aspect of offering something to viewers that they will have to rearrange for themselves. It’s a very different film each time you view it.

R: In Counting there are places that you have never seen before and there’s a lot of New York, a place where you’ve lived most of your life. And I think to see a difference in the way the material looks. Do you still have the same curiosity and sense of discovery when you walk through New York, and do you look at new places differently or alike?

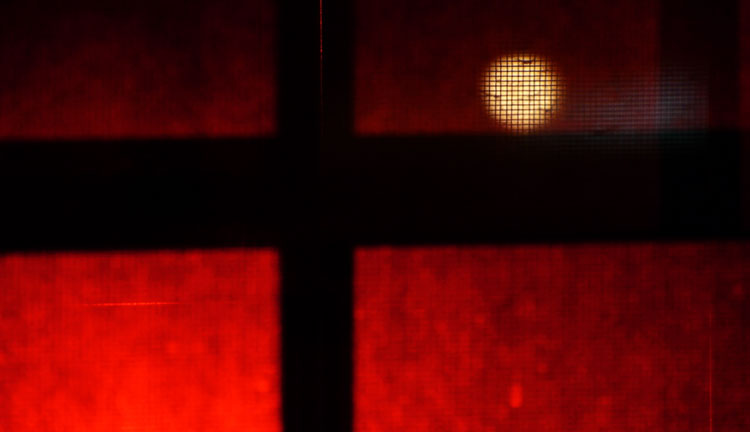

JC: On a good day the process is kind of similar, because if you open your eyes and your ears wide and you’re able to do that with a kind of non-judgmental fascination, then any place can be quite interesting. That said, the New York sections are different. Particularly in the first section, there’s more abstraction. There’s a non-linear tumbling together of memories and familiar moments with the kind of extremes that you still find in a city that big and in a way, insane. I don’t ever want to become bored in the places that I’m familiar with and filmmaking helps ensure that that never happens. If I was a more kind of theoretical person then I would be able to give you a better philosophical or at least a clearer answer as to what the differences are between these sections. But I know that they’re different. And the last section, which, again, was the first that I made, is also a different voice, it has a different purpose. I don’t identify the location in the last chapter, because it’s not longer about portraying a particular city. It’s about about a life’s work, it’s about a process, it’s about being in all of the cities in which we are strangers. I tried to make sure that the different chapters had different forms and different functions. But eventually they’re different angles on a somewhat unified whole, I think.

A lot of these projects, they’re kind of from the gut or from the heart and they’re not the kind of thing where I scripted them or had to pitch them or found ways to force them into some acceptable package. I’m trying to find some freedom in the making. It’s like, bad improvisation in music can be just a mess and it can be self-indulgent. With good improvisation, you have the sense that somebody could play it straight if they wanted to, but they are sort of jumping off of a cliff with curiosity and with a kind of faith that something will come alive.

R: That means the structure of Counting came about in the edit?

JC: These are the kind of things that could not be decided in advance. One of the shortest pieces is in Porto / Portugal and it’s a kind of light interlude, but it’s also a challenge: “Here I am. I’m walking in a place I’ve never been… I take a turn into this alleyway. I have just an hour and a half or two… Alittle play, starring some animals takes place and that’s what I witness, and that’s what I document”. And that’s all that that will be. Another chapter’s really just the light on someone’s face in my apartment and that’s all that it’s meant to be. In other chapters there are bigger matters, even if it they are again discovered through found theatrics.

The little section in Red Square is also just based on an hour or two spent there, but it of course touches on some rather enormous topics, because how can you not touch on those topics, when you look to the left and you notice that there’s a bust of Stalin, with flowers on it. (laughing) I didn’t go to Red Square intending to make a film having anything to do with Stalin and I didn’t call it “The Millions” until I had finished the section in the edit.

R: You chose to give the chapters titles, to put them or contextualize them in words, whereas you could have also just numbered the chapters. How did that choice come about?

JC: Sometimes there’s an identification of time and place, sometimes a pun or aphorism.

It’s a way of thickening the plot, of reflecting the Zeitgeist, such as when I indirectly refer to the NSA, the CIA, and the FBI with the title “Three Letter Words.” (In the U.S., “Four Letter Words” is a generic term for obscenities.

R: During the working process, over time, the layers of ongoing political events and Zeitgeist of sorts make their way into the material, and you actively make it part of the image and sound information in some chapters. So the film correlates with and shows a specific time.

JC : In that NSA chapter I wanted to underline, to throw my own particular spotlight one of the most outrageous moments I’ve ever witnessed, in which the director of so called Intelligence for the entire U.S. government blatantly lied to Congress and the American people. There’s historical specificity there, but it’s also not like these occurrences are going to go away. We have entered into an era of global surveillance, and it’s just about inconceivable that it will ever go away. There’s a kind of portal in the last few years, in which it becomes very important to mark the moment, to mark the way in which it enters the atmosphere of daily life. And on one hand some of these reference may become dated. But I’m not only talking about specific events. I’m talking about recurrence; about the way things continuously resurface. And that is to some degree what I’m „counting” in the film. And I hope that it gives it some currency in years to come.

R: To talk about your protagonists – how do you approach people like Benjamin Smoke or Bobby Sommer for example? How do you start including them in your films?

JC : I was lucky to meet Benjamin, lucky to meet Bobby. But also, I don’t think that I did anything so special. I mean, the world is full of very interesting and beautiful people. If I get on the subway, in New York, Paris or in Moscow, I can’t imagine being in even a moderately crowded subway car and not finding five people that I would be utterly fascinated to follow and to speak with and to see what their homes are like and to find out something about what they’ve experienced. I think it’s very strange that we put so much of our concentration on celebrities, or certain kinds of powerful people, when so many people are so extraordinary. You just have to look carefully. I’m pretty shy in person. But, I can’t even begin to say how many times I’ve seen people who just stopped me cold, because their face or eyes were so amazing. And they’re just people that you pass on the street. So, I don’t think I’m doing anything that unusual. I mean, Bobby had a beautiful voice. And I used him to read Joseph Roth texts in a project called Evening’s Civil Twilight in Empires of Tin prior to Museum Hours. And I could tell as he read, that I would love to work with him. And also it became very valuable that he had a broad life experience, that he had done a lot of different jobs. Some of them interesting, some of them not. But, he had experience. And so that then becomes valuable, in a character in a film.

R: Did the idea for Museum Hours come from the place – the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna itself or from thinking about specific people or something else?

JC: The initial impetus came from the Bruegel room. I’m not obsessed with Bruegel, but I became quite hypnotized by a familiarity that I felt standing in front of his paintings. And it was a familiarity about documentary and about street life, and also a recognition of commonalities. It doesn’t matter the century. It doesn’t matter the city. It’s just, people are people. And, landscapes are landscapes. Light is light. Weather is weather. Dogs are dogs. (laughing)

R: Could you describe how you developed the dialogues and the narrative of the friendship in Museum Hours, to which extent it was scripted, improvised or a mix of both?

JC: It’s a mix. Sometimes, it’s very carefully scripted. Sometimes, one person is scripted and the other is not scripted in any way, and they’re just free to respond. Sometimes I’m showing footage that I’ve already shot and telling somebody to pretend that they’ve seen it and describe it. It’s a mix. I just ask myself a simple question, which is: How do people really talk? And how are friendships really forged? And why not have a movie that investigates the connections that people can have, that are not only about everybody counting down the minutes before the beautiful people kiss?

R: How was the shooting process of Museum Hours, what about shooting chronology, the work with the actors etc., compared to for example Chain?

JC: It’s less different than you would think. There is a certain degree to which I think it can be helpful to actors to try to not jumble things up too much. But a lot of the movie was ordered in the edit. I had some things scripted, but I never handed anyone a completed script. And so, the important thing was really to gather the people and put them into these locations and then always to allow for the possibility of the real world to intervene. We were rarely in permitted locations. We were shooting in the museum when it was open, except for the nude scene. And we encouraged a kind of loose interaction between the acting and the script and the world. Sometimes you run the risk of losing a scene that way, but you also gain the wonderful chance encounters and moments that you wouldn’t have if you locked everything down.

R: The scene when the two of them meet in the bar, did they have some prompts what they should talk about, or how did you go about that, for example?

JC: I knew that I needed somebody to talk about certain things, to touch on certain things. And then, I also know that these are complicated people who’ve had interesting lives and if given some freedom then they’ll bring some of that along. The most important thing was that I didn’t want it to be obvious which things were improvised and which things were not. I might have said, “I want you to have a conversation and in that conversation I want you to admit that you’re a fan of Heavy Metal.” But I certainly didn’t tell anybody to bring up the name of Judas Priest, you know? (laughing)

I mean, it’s not the only way to go about things. There are wonderful movies that are completely scripted. I don’t really think that that’s a mistake for somebody else to do it that way and I can’t say that I won’t ever do it that way. But I often tell people, and I don’t know if they believe me, that Museum Hours was not a departure for me. It’s just a continuation of what I was already doing, and then Counting is a continuation again, on the other side of it. And in terms of the industry, maybe there was some disappointment with Counting because people thought, “Oh, he’s made a movie (Museum Hours) that looks more like a real movie and actually did surprisingly well, in the U.S. theatrically…” And so, I think, people thought that I would ramp it up for the next one and maybe get some name actors in there, etc. but I didn’t. I stripped things way back instead.

R: In terms of narration and “predictability”, comparing Chain to Museum Hours, I would even say Chain looks more narratively composed than Museum Hours for example…

JC: Well, I got better at what I was doing. But Chain is where I was taking the leap into that mixture… When I was shooting Chain, there was absolutely no possibility of getting official permission to shoot in any of the shopping malls. And that’s largely what the movie was about. (laughing) So, I had to find ways to just drop the actors in to the real world. It’s very difficult, honestly, because, when you create a bubble with actors in it and controlled locations people will accept almost anything that happens within that bubble. But when the real world kind of crashes in, it can suddenly become very uncomfortable, because you realize just how phony the movies usually are. And the audience sometimes wants what they’re used to.

I think it’s largely because people have been trained that way – by cinema. That was one of the hardest things about Museum Hours, to just to have a man and a woman in the frame together. They meet for the first time and there’s just this ridiculous expectation that you are going to do romance now. It was very tricky to veer away from that without disappointing people, and I wasn’t trying, gratuitously, to refuse to satisfy. And what I think we were lucky with was that we were able to actually create a movie where the environments and the ideas were really just as important as this story. But we did it very quietly, so that people watching the film don’t necessarily notice that anything strange is happening. Until it is too late. (laughing)

R: You always set out to make a film about friendship, about an encounter, I imagine?

JC: It becomes a little bit embarrassing over time to look at so many movies and realize that a simple idea like friendship or mutual curiosity is so rarely seen as acceptable subject matter, you know?

I listen to all different kinds of music. I listen to beautiful and violent and mysterious and ancient music, and I can’t imagine limiting the resonance of the music. But we’ve somehow accepted to a large degree to limit the resonance of what the movies are generally about.

And I don’t feel that filmmakers are doing that. I think that there’s an extraordinary amount of interesting filmmaking that‘s always happening, and when you go to a good film festival you get a real cross-section of it. But there’s this battle that brings us around to where we started, in terms of funding and the industry and pitching and all that, when it comes down to: Are we going to limit the resonance, the frequency range, to use musical terms, or not?

I learned a tremendous amount from watching Cassavetes’ films, where I was put in immense discomfort, because of never knowing how they were going to end. It’s very different from what I do and they’re in some ways by necessity much bigger movies, with ensemble casts. But he had the guts to stubbornly refuse predictability. And I think that that was very important for me to encounter. But I was also encountering it anyway every day, because that’s what life is.

And so, again, to get back to Counting, there’s just nothing so difficult about the film. There’s nothing prohibitive about it. It’s not talking in a language that is rarefied or only accessible to people who have studied film theory. It’s just a kind of stubbornness, repeatedly turning the wheel towards what I believe to be common experience that humans have. We live in a constant mixture of emotions and memories and incredibly small moments, some of which are very, very enigmatic and beautiful and many of which are disturbing. But I wanted to make a film in the forest of that relentless unpredictability.

R: I can see that musical element in the editing of your films. Did your interest in music in some way influence your way of editing?

JC: I teach editing sometimes by playing music rather than looking at films. There’s no question about it, many of my friends are musicians and I’m astonished by what they’re able to do. And I’m not a musician. I’ve never played an instrument and I think that to some degree I’m trying to make music in a different way. Sometimes by eliminating music altogether. But doing it through durations and rhythms and collision and echoes. I learn from music all the time. I learn from every kind of music. I probably learn as much from music and painting as I do from other people’s movies.

R: While you edit the image, do you work on the sound design yourself? Because you have voice over, you have diegetic sounds, you add additional music that correlates to the images.

JC: I have to make some adjustments as I work, even if I know I’m going to do it properly later. I have to go in and do some color correction and sound mixing, because otherwise, how would you know if it’s going to work? I was very lucky and thankful to work with great sound engineers on these last couple of projects and with Counting we did some very interesting things, because the sound person can do them much better than I can and has interesting ideas of their own. But I generally lay the groundwork by myself.

I can’t separate the production, the rough-cut, the sound work, the color. It’s just so alien to me to think that you can consider them separate. It’s like you’re making a meal but you don’t allow yourself to taste it as you prepare it. It’s just not possible to me that you could know that it worked, if you didn’t get your hands dirty.

I was getting a little bit disheartened at the beginning of the conversation and started to feel like I kind of built this little prison for myself, by having to make films my way. But it’s also really fun in here. (laughing)

I love the work. I love the mystery of it. I mean, when I see a Bresson movie, it’s like walking on another planet. In a very beautiful way. And, I’m just blown away by that. So, it’s not like I want everything to be the way that I, personally, would do it.

R: A question on analog and digital filmmaking. How do you choose to shoot either analog or digital, apart from financial reasons, and do you have self-imposed rules of sorts when you shoot digital?

JC: I shot film for so long, it’s kind of in my blood. There’s a certain discipline that you learn, because film was always expensive. And now I’m happy to have had that discipline, but also happy that I can occasionally contradict it. Because I’m thrilled that I can sometimes let the camera run and run and let things happen within the frame that I would’ve had terrible limitations with, if I was shooting with the Bolex, for example, with a 25-second limit per shot.

I will never get over the loss of film as film. There’s something about the irregularity of the grain and the basic language of interpretation of light, which is in some ways beautifully removed from the way that we actually see, rawer or more interpretive. But I have never been able to be a purist, because logistically that would have limited what I can do. And I’m very, very concerned about what I can do. AI’m determined to shoot some film as long as it is possible to do so. But that’s very difficult now, financially, and it’s difficult because there’s no wet lab in New York. Believe it or not…

So every once in a while I have to remind myself that some of the most beautiful films that I saw in the past ten years, for example, was Pedro Costa shooting with a MiniDV. And translating that to 35 mm film. Somewhere in there it became incredibly beautiful. It was such a low-end format. It’s just astonishing. I think that there are many beautiful things yet to come.

R: Do you actually still shoot Polaroid photos?

JC: Polaroid was the great love of my life and for many years I just did it quietly as something that I found the strangest secret pleasure in. Especially the loss of Color 600 Film and SX 70 is rough for me. Because I loved it very much and I was really spending money I didn’t have to buy Polaroid film before it was gone. Now the few rolls that I have stashed away, they’ve gone bad. I shouldn’t have waited… (laughing)

R: Did you actually start with filming or taking photos?

JC: I think the first image-making that I did may have actually been regular 8mm films, animation films. And I did 35mm still photography when I was quite young. I didn’t go to film school, but I shot 16mm to make my thesis project for Wesleyan University. Actually, they had very little film production so I left and got a job as a shipping clerk and film repairer at a small company where I could borrow equipment, and made the first film that way. When I left school 16mm got too expensive and I started shooting Super8. And then I shot both for the next twenty-five years. But I could almost never finish on film, it was too expensive, so I’d edit and finish on video, alas.

R: I saw Counting at the Viennale. After the Q&A you walked out of the cinema carrying a camera?

JC: Yes. I carry a camera with me almost all of the time.

The conversation was conducted by Zsuzsanna Kiràly in November 2015 via Skype. Translation: Zsuzsanna Kiràly, edit: Zsuzsanna Kiràly and Marcus Seibert. Find the German version of the interview in Revolver Issue 34.